When Andrea Caruso joined Casa Cornelia in August 2000 to coordinate the asylum program no one could have anticipated the events that were to transform the program at Casa Cornelia Law Center for the next two years. At the time of her hiring in the spring, everyone anticipated increased activity at the port of entry. Certainly, it was thought that most of her time would be committed to border interviews and representation of refugees in non-adversarial interviews with asylum officers at the San Ysidro Port of Entry.

No one then imagined that San Ysidro would become the port of entry for hundreds of Chaldean Christians fleeing Iraq. In retrospect, perhaps, it should have been no surprise. El Cajon, a municipality twelve miles east of San Diego, is one of two cities in the United States with significant populations of Chaldean Christians, Iraqi. Only Detroit, Michigan and Baghdad itself are home to more Chaldeans.

The Chaldean Christian community is an ancient faith community that is in union with the Roman Catholic Church. The language of the community is spoken by Jesus himself and the community’s culture and faith are deeply rooted in the beginnings of Christianity and the ancient territory between the Tigris and Euphrates.

Prior to the Gulf War, these Christians were barely tolerated in Iraq. Following the war, when the impact of sanctions began to weigh heavily, they became a very vulnerable minority. The young men were harassed, imprisoned, and sometimes tortured. Chaldean businesses became the target for shakedowns and recriminations. More and more pressure was placed on the families to join the Ba’ath political party and to convert to Islam. The young men became victims of discrimination and persecution during their compulsory military service.

Prior to the Gulf War, these Christians were barely tolerated in Iraq. Following the war, when the impact of sanctions began to weigh heavily, they became a very vulnerable minority. The young men were harassed, imprisoned, and sometimes tortured. Chaldean businesses became the target for shakedowns and recriminations. More and more pressure was placed on the families to join the Ba’ath political party and to convert to Islam. The young men became victims of discrimination and persecution during their compulsory military service.

Escape began to be the only viable option for many, although the exodus north from Iraq through the Kurd territory and into Turkey was perilous. The refugees were not welcome in either territory. In Turkey, they were without status and subject to arrest and deportation. Some remained there nevertheless; others continued their journey to Greece. Greece seemed less dangerous and more stable.

The refugees could not secure legal status in Greece, but their presence was tolerated. In Greece, there was also the hope of securing UN refugee status and possible emigration to a third country. With lengthy delays and disorder in the processing of refugees by the Greek government, the refugees became desperate. The futility of their position eventually prompted the refugees to take matters into their own hands. With the financial assistance of family members, the refugees made arrangements to secure documents and visas to Mexico, and then to America.

By the fall of 2000, the Chaldeans were routinely interviewed for asylum at the Mexican-American Border. During the processing and approval period, they resided in hotels in Tijuana. Family members from the United States visited them. Although they were impatient to have their sojourn come to an end, the asylum office was approving virtually all their applications.

This situation changed dramatically and abruptly in September 2000 when Mexican immigration authorities stormed three hotels, arrested the families, women and children, and detained them in the Tijuana jails. The Chaldean community in El Cajon was outraged. After a media blitz that focused on the deplorable conditions under which the refugees were being detained, the Mexican government finally agreed to release the families on the condition that they would present themselves to INS officials at the border.

Bus loads arrived at the port of entry. The families once again requested asylum. They were then fingerprinted, photographed, placed into shackles, and detained in a maximum security prison at the border. Over two hundred men, women, and children were detained after having fled the oppressive regime of Saddam Hussein. Most had been en route to freedom for over three years. Until counsel could be found no, final resolution was possible. It was a nightmare.

It was clear that Casa Cornelia could not commit to representing all who needed legal representation. It was also evident that certain unscrupulous individuals were prepared to prey on the vulnerability of the asylum seekers. Aware that there were competent and committed individuals within the immigration bar who had experience in defensive asylum work, Casa Cornelia recruited some ten attorneys who agreed to take cases at a significantly reduced fee. The understanding was that Casa Cornelia Law Center would screen all the prospective clients, and provide support documentation, interpreters, and case management.

For the time being, the crisis was over. The refugees were released on their own recognizance and the trials went forward. The Asylum Office resumed interviewing newly arrived asylum seekers at the border. Things proceeded smoothly, until September 11th.

On September 11th over one hundred fifty Chaldean Christians were waiting in Tijuana hotel rooms for interviews with Asylum Officers. With few exceptions, all the refugees had submitted their formal requests for relief. For them, as for the rest of the world, September 11th began like so many others and then everything changed.

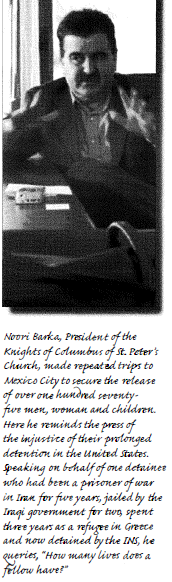

The Mexican immigration officers once again swept through the hotels, loading the terrified refugees into busses and then into airplanes. With no opportunity to contact their families or friends in the U.S., all the Chaldeans in Tijuana were transferred either to jails in Mexico City or to a refugee detention camp near the Guatemalan border. Fears ran high that they would arbitrarily be removed to Iraq and certain death. Negotiations to bring these refugees to the U.S. border for asylum processing dragged on for three and one-half months. Their U.S. families worried about their health and well-being, of special concern were the women and children.

The Mexican immigration officers once again swept through the hotels, loading the terrified refugees into busses and then into airplanes. With no opportunity to contact their families or friends in the U.S., all the Chaldeans in Tijuana were transferred either to jails in Mexico City or to a refugee detention camp near the Guatemalan border. Fears ran high that they would arbitrarily be removed to Iraq and certain death. Negotiations to bring these refugees to the U.S. border for asylum processing dragged on for three and one-half months. Their U.S. families worried about their health and well-being, of special concern were the women and children.

Finally, days before Christmas, the Mexican government agreed to return the refugees to Tijuana in groups of twenty with the understanding that they would present themselves immediately to U.S. officials at the port of entry.

Casa Cornelia Law Center staff attorneys met with the leadership of the Chaldean community and agreed to make a “best effort” to persuade the immigration attorneys to step up to the plate one more time. To a person, the attorneys agreed. By week’s end, Casa Cornelia Law Center had a commitment to represent at least thirty of the seventy-five cases. Best guesses also indicated that at least fifty percent of the Chaldeans would be seeking a change of venue to Michigan. Casa Cornelia agreed to prepare all motions for a change of venue.

Unfortunately, the detention of this group of refugees over the next four months made it extremely difficult to provide legal representation for these asylum seekers. All of Casa Cornelia’s staff attorneys have been involved in assisting these refugees. Deborah Mancuso, a volunteer attorney, has recently joined the attorney team to help with those Iraqis who remain in detention. Andrea Caruso, however, was the heroine in the piece. Her jottings provide a sampling of the many ups and downs of keeping the asylum program moving along.

Jorge –

(Guatemala) Sent north with false docs to the asylee’s aunt in SF because he was threatened with kidnapping. Apprehended at the border and intimidated by the inspector so expressed no fear of return. The officer told him he would go to jail for one and a half years for using false docs. Accompanied through credible fear and assisted with the posting of bond. Granted asylum in San Francisco by an immigration judge. Case Closed.

Martha –

(Honduras) Widowed with four children by Hurricane Mitch. Traveled north with her brother but became separated. Gets hooked up with coyotes who drug and rape her. Eventually rescued by border patrol. While in detention learns that she is pregnant. We obtained her release without bond and a delay of deportation until her son is born. Case closed.

Ramzi-

(Chaldean Iraq) Repeatedly jailed on suspicion of opposing regime because of brother’s anti.,.government activities. Brother executed, client flees. Smuggled to Mexico from Greece, interviewed and denied at the border by asylum officer because of bias against Chaldeans. Immigration Judge grants asylum in a hearing that takes less than thirty minutes. Reunited with wife and son in San Diego. Case closed.

Amina-

(Chaldean Iraq) Sixty-seven-year-old illiterate woman. Ba’ath military officer forcibly converts her younger son to Islam while in the army. Also forces him to marry his daughter. Party members and the girl’s family repeatedly attack Amina and her husband to force them to convert. Her husband dies from a blow on the head. Held for three weeks in maximum security prison because her file was misplaced. Granted asylum by Immigration Judge. Case closed.

Athir-

(Chaldean Iraq) Arrested on suspicion of opposition activities because of participating in a young men’s church group. Arrested for the second time when the employer was arrested for political activities. Witnessed execution of employer. The client was beaten and sent to hospital from which he escaped. Denied at the border by the same asylum officer. Case denied.

Ivian-

(Chaldean Iraq) Young mother fled Iraq when security officer was killed in husband’s restaurant. The officer’s brother kills her parents-in-law when he cannot find the client’s husband. She came to the Mexican border with her two daughters ages one and three. They are taken into custody when the Mexican government threatens to deport them back to Iraq. Granted asylum by the Immigration Judge but the INS appealed the decision. Case pending.

Amina-

(Somalia) The client was nine years old when USC [United Somali Congress} attacked home and beat her and her family. Fled to a refugee camp and married. Smuggled to US in 1999 and denied asylum because of the ineffective assistance of a counselor. CCLC filed a motion to reopen and undertook representation. Incarcerated by INS for over nine months. Upon presentation of new evidence, IJ grants asylum. Once again, INS files what appears to be a vindictive appeal. Client working in a hotel in Minnesota. A $30,000 bond cannot be released until the appeal is resolved. Case pending.

Abdu-

(Ethiopia) Journalists and educators spoke out in favor of Oromo self-rule. Arrested for political activities. Brother part of the rebel movement. Loses kidney and eyesight as a result of torture and conditions in prison. Flees to Kenya. Wife dies in Ethiopia and mother brings five children to Kenya refugee camp. Granted asylum. Currently engaged to another asylum seeker and working to bring children to U.S. Case closed.

Dilkhwaz-

(Kurdistan) Women’s Rights Activist previously detained and tortured by Saddam regime prior to Kurdish independence. Travels to US to speak at the conference. Statements critical of Islamic fundamentalist parties. Reported in Kurdistan and receives death threats from Islamic party. Granted asylum. Case closed.

Sivad-

(Somalia) USC clan attacks the village and kills the father and husband. Client subjected to repeated rapes. She flees to refugee camp and eventually is smuggled into the US. Denied asylum in 1999 at the asylum office. Marries Ethiopian who is a permanent legal resident and gives birth to US citizen daughter. While in hospital with pregnancy complications she is ordered deported in absentia. Motion to reopen filed. Judge grants administrative closure. The husband becomes a citizen and can now emigrate her, sparing her from telling her tragic story in court. Case closed.